As we all know, in addition to numerous health and fitness benefits, one of the key benefits of martial arts training is in allowing us to gain valuable self-defense skills. Those skills go with us wherever we go, and are at our disposal should a situation arise – at home, in school, at work, at play, and even on travel. The other aspect of developing deep-rooted self-defense skills is in allows us to gain confidence in different situations. With this confidence, we are better able to identify, avoid, and diffuse threats well before they escalate into a physical altercation. However, gaining self-defense skills takes dedication and work. This is partly because our body instincts, which serve us well in most situations, are sometimes in conflict with what constitutes a solid self-defense response. For example, you probably heard about our “fight or flight” reflex. On one hand, this reflex injects adrenaline into our body, which makes us better able to move rapidly and to sustain pain. However, the “fight or flight” reflex also causes “tunnel vision” – a direct focus on the perceived threat, to the exclusion of seeing the “whole picture”, and this focus can severely handicap us in self-defense situations. So what can we do? In this blog we explore some of our natural instinct, discuss how they serve or hamper our self-defense response, and how martial arts training strives to teach us the correct response.

The Aim of Self Defense Training

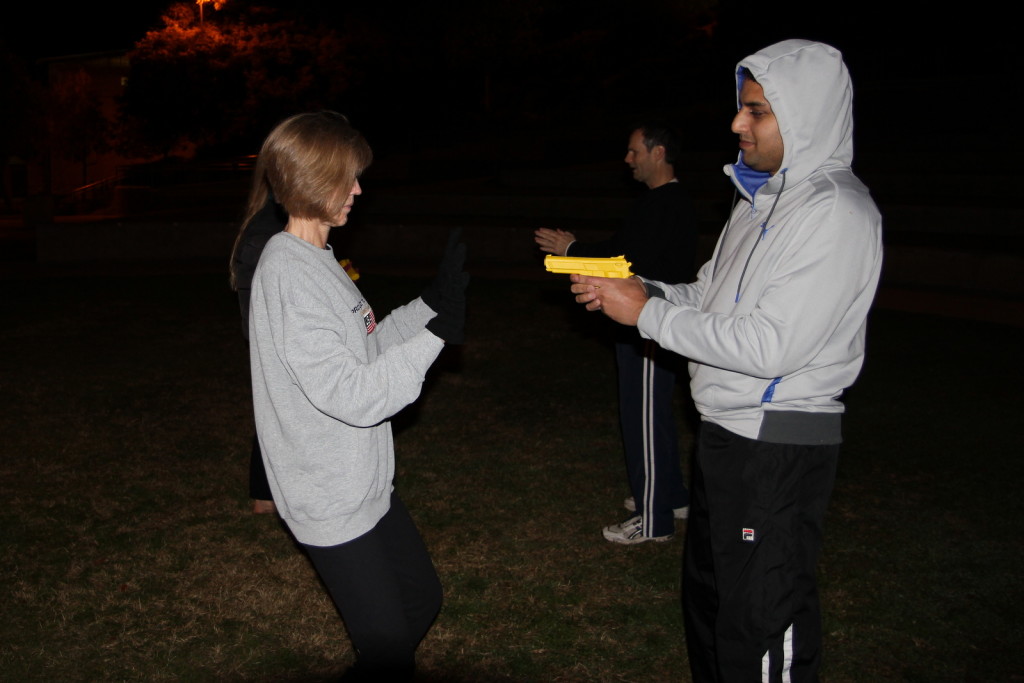

Much of the aim of martial arts and self defense training is to instill the proper instinctive responses in us. Self defense isn’t really about “how many techniques you know”, but rather about how skillful you can be with what you know. By that I mean that it far better to know a handful of techniques, and be able to deploy them under high levels of stress, than to have precursory knowledge of a large number of techniques. As an aside, I should mention that psychologists have long known that human response time greatly escalates the more choices are present (see, for example, Hick’s Law, circa 1952, so named after British psychologist W.E. Hick). For these reasons, in self-defense we aim to train our brain and bodies to act instinctively, rather than to have to make conscious decisions. We also aim to train a deep sense of calm, since maintaining calm improves our performance in the face of adversity.

Our Reflexes

Recognizing our human (and, as we shall see, animal) reflexes, their benefits and disadvantage, helps us in self defense. Generally speaking, in self defense training we aim to recognize, and mitigate, the hard-wired instincts that are detrimental to us, while learning how to induce, and take advantage of, those same reflexes in our perpetrator. We will come back to this point after discussing specific reflexes. But first, let us sort some terminology. I will loosely use the term “reflex” here to refer to involuntary responses, although in the strict term, some of these responses are more complex than simple reflexes. The important thing to recognize is that our reflexes are deeply rooted in our nervous system and, in fact, can be found in the nervous systems of animals or even simple organisms such as amoebas. That means that serious and directed training is needed in order to counteract them.

The following reflexes are useful to understand in the context of martial arts and self defense:

- The startle reflex (also called startle response): We all know that, in response to a sudden noise or sharp movement, we tend to startle. This is a brainstem reaction that serves to protect the back of the neck, and to facilitate escape from the stimuli. If you have been startled by a friend or relative you know what I mean – your body stiffen, shoulder rise, and attention snaps. We will discuss the implication of the startle reflex to self defense in further detail below, as it is one of the most difficult reflexes to (un)train.

- The balance reflex (also called righting reflex): This is our natural response to want to maintain upright posture and not fall. During a fight or physical altercation, it is critical to maintain balance at all times. When we feel that we are falling, our balance reflex (like the startle reflex) will cause our bodies to stiffen and tense. In fighting, this stiffening is counterproductive for a number of reasons. First, if we are to fall, it is better to fall in a relaxed and natural posture, allowing the impact to dissipate throughout out body, rather than be concentrated in one point. Second, when our body stiffens up, it is much easier for us to be thrown (Judo master Kyuzo Mifune demonstrates this concept beautify in the video on our blog here — observe how, by being relaxed, he is virtually impossible to throw). From an offensive perspective, we seek to induce the balance reflex in our perpetrator, causing the partner to stiffen and become an easy target for a throw. Also, by constantly keeping our partner feeling like he or she is about to fall, the partner is preoccupied with righting themselves rather than attacking us. As we have seen numerous times in class, Okinawan martial arts such as Karate, as well as Chinese arts such as Kung Fu and Tai Chi, seek to establish control over the opponent’s center at the beginning of a fight, thereby allowing us to unbalance the opponent.

Implications of the Startle Reflex and the “Fight or Flight” Response

Different animals react differently to being startled. Consider the following photos, of a deer and a bobcat. While the deer perks up when startled, the bobcat response to a threat is to crouch down.

Unfortunately, the untrained human response to a threat is more akin to the deer’s response – we tend to perk up and tense. Through martial arts training, we seek to be more like the cat than the deer, i.e., to drop our center and relax at the face of a threat rather than tense up and rise. This is not easy, and takes a lot of training (and, even with a lot of training, in a real situation there is no guarantee that we will not “freeze”). The reason has to do with how our autonomous nervous system works. The human autonomous nervous systems can be divided into three parts: the parasympathetic nervous system, the sympathetic nervous system, and the enteric nervous system. The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for regulating internal organs and glands. Specifically, those relate to “rest-and-digest” activities such as salivation, digestion, tearing, etc. On the other hand, the sympathetic nervous system is responsible for priming the body for action in our fight-or-flight response. In response to stress, the sympathetic nervous system counteracts the parasympathetic nervous system. This affects almost every organ in the body, and is responsible for such broad responses as dilating the pupils of the eyes, increasing our heart rate and blood pressure, tensing our muscles, and decreasing our gut mobility. (The third part of our nervous system, the enteric nervous system, is responsible for governing the functions of the gastrointestinal system. We will ignore it for the purposes of this self defense discussion.) For optimal performance, we would like our response to stress to be governed by the parasympathetic nervous system, rather than the “fight or flight” response of the sympathetic nervous system.

The table below summarizes the differences in response to a threatening situation between those who are not trained in self defense, and those who are trained in self defense:

| Untrained Response | Trained Self-defense Response |

| Body is tense | Body is relaxed and ready for rapid response |

| Pupils dilate; vision is focused on threat. The higher the threat, the stronger the “tunnel vision” effect. | “Soft focus”, grasping the “entire picture” |

| Shoulder rise | Shoulders drop |

| Body rises | Body drops (low center of mass) |

| Counter force (e.g., being grabbed or pulled) with force | “Go with the flow” and execute a technique |

| Freeze — “deer in the headlights” | Flow |

| Think | Do – allow the training to come out |

It is interesting to note that, in the modern world, we find ourselves in stressful situations quite frequently. Of course, most of the time, those are not because we are under physically threat, but rather because our body’s reflexes are triggered by modern-life induced stresses, such as a relationships with a boss of colleague at work, a teacher or another student at school, a boyfriend, girlfriend or spouse, a test, a deadline at work, or other stimuli that elicit a visceral stress response in our bodies. The added benefit of self defense and martial arts training is that it gives us the tools to deal with these types of stresses as well.

Keep on training and remember to “be like the cat”!

“Be Like the Cat” – I really like how that was phrased.

I found the article to be quite interesting and especially liked the table representing (an Untrained Response and a Trained Self Defense Response).

I also like the philosophy written in the article behind Martial Arts and Self Defense, it’s not how many techniques you know; it’s how well you can execute what you know.

Lastly, looking forward to increasing my parasympathetic nervous system to take over and react correctly during stress, if the need should ever arise.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge and experience.

These arts can help you in a life or death situation. If i am to protect myself or loved ones, I want an art that focuses 100% on survival techniques in worst case scenarios, not a sport that can “Help out”